Is Animation Art Dead? Not By A Long Shot!

Is the animation art industry ready to bring out the pig to stutter his final “Th-th-that’s All Folks!” as the pundits would have us believe? Having spent our lives with passionate confidence in the importance of the art of animation and its enduring quality, we would heartily disagree. As with any business, it has had its ups and downs while it deals with changing markets and an increasingly sophisticated audience. But those who bet on its demise will undoubtedly find themselves in the position of Wile E. Coyote as he tries, for the hundredth time, to snare the Road Runner in his Acme booby trap. No amount of dynamite is going to stop this bird.

Is the animation art industry ready to bring out the pig to stutter his final “Th-th-that’s All Folks!” as the pundits would have us believe? Having spent our lives with passionate confidence in the importance of the art of animation and its enduring quality, we would heartily disagree. As with any business, it has had its ups and downs while it deals with changing markets and an increasingly sophisticated audience. But those who bet on its demise will undoubtedly find themselves in the position of Wile E. Coyote as he tries, for the hundredth time, to snare the Road Runner in his Acme booby trap. No amount of dynamite is going to stop this bird.Much of the current gloom is based on the fact that the animation art market has not returned to the stratospheric prices it was commanding at auctions in the 1980s. Animation art is so well respected now as a legitimate art form that many people are unaware that it was never seen in the major auction houses or museums until 1984. The value of this truly American art form was brought to the public’s attention when the collection of John Basmajian came onto the market.

Basmajian was an animator for the Disney Studio during the World War II years. The Disney Studio had turned its full attention to aiding the war effort producing animated films and other graphics for the armed services. The storyboards, backgrounds, concept paintings and cels were stored in a room called “the morgue” which had to be cleaned out to make room for war work. The animators were given permission to take whatever art they wanted, rather than destroy it, and Basmajian rescued a large amount of material from the earliest Disney films. He recognized the beauty and importance of the drawings and paintings used in the production of the Silly Symphonies, Snow White, Pinocchio, and Fantasia. He spent the rest of his life experimenting with techniques to preserve the original art.

When he offered his collection of about 400 pieces to Christie’s East for an auction in 1984, he unveiled an unprecedented treasure trove of perfectly preserved production art, with complete sets of cels and backgrounds keyed together. The auction ignited the interest of serious art collectors and kicked off a boom in the sales of animation art that drove prices to levels never imagined possible.

As the baby boom generation began to buy artwork, they naturally gravitated to the bold images of the cels used in their favorite TV cartoon shows from the 1960s. The manic energy of the Hanna-Barbera cartoon cels appealed to the generation that came of age grooving on prime time cartoons such as The Flintstones and The Jetsons. The movie theaters also ran at least one cartoon film short before the main feature and that was often a Looney Tune starring Wile E. Coyote and Roadrunner. As an appreciation for animated films and TV shows hit its peak, the animation art market naturally grew apace. It hit its high point in June 1989 when Sotheby’s auctioned the art from the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit?. The prices realized were often two and three times the projected estimates.

This new level of interest in animation art was swiftly followed by the release of four Disney blockbusters: The Little Mermaid in 1989, Beauty and the Beast in 1991, Aladdin in 1992 and The Lion King in 1994. The success of the films spurred the animation art market to ever higher levels, creating a demand not only for the original production art, but for related artwork in the form of limited edition series and fine art giclées. These made it possible for many more people to collect the art by offering lower price points than originals were commanding. Thus a family could bring home the same wonderful characters who brought them joy in the movies but at a very affordable price. The giclées were produced on canvas and gallery wrapped around stretchers so that they didn’t even require framing.

This new level of interest in animation art was swiftly followed by the release of four Disney blockbusters: The Little Mermaid in 1989, Beauty and the Beast in 1991, Aladdin in 1992 and The Lion King in 1994. The success of the films spurred the animation art market to ever higher levels, creating a demand not only for the original production art, but for related artwork in the form of limited edition series and fine art giclées. These made it possible for many more people to collect the art by offering lower price points than originals were commanding. Thus a family could bring home the same wonderful characters who brought them joy in the movies but at a very affordable price. The giclées were produced on canvas and gallery wrapped around stretchers so that they didn’t even require framing.One of the pioneers of the limited and special edition market was Linda Jones, daughter of the master of animation, Chuck Jones. Chuck Jones animated the most beloved Looney Tunes, among many other cartoons, in a long and brilliant career. Linda, who was an Emmy award-winning producer in her own right, worked with her father on cartoon films for Warner Brothers and was involved in every aspect of the business. Her son Craig Kausen continues the tradition by curating his grandfather’s art and overseeing the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity.

As Kausen has taken over the reins of Linda Jones Enterprises, he’s seen a resurgence in appreciation for an art form that makes a personal connection to people who grew up enjoying the cartoons. Kausen observed first hand that “When you look at animation art it brings a smile to your face and just seems to make life easier. It is a purchase of joy and although the art more than holds its value, most people won’t part with it.” There is a new appreciation for the historical significance of the artwork which, in Chuck Jones’ case, set a whole new direction for animated art, just as the Impressionists had done for painting, a hundred years earlier.

Several factors have contributed to the recent resurgence of interest in animation art. The continued success of the prime time TV shows The Simpsons has inspired many more animated shows intended for an adult audience. After a fairly dry spell of reality programming, television is finally returning to the scripted comedies, many of which are animated. Just as Walt Disney was certain that adults would flock to see a feature-length animated film, Snow White in 1937, today’s audiences are tuning in to the animated shows in record numbers. This must be a real trend when both Warren Buffett and Glenn Beck are in discussion to star in two new animated series.

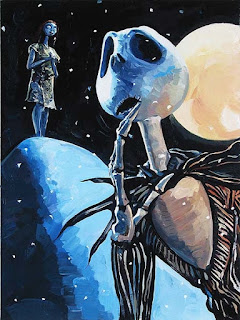

In the movie theaters, a new era in animation was introduced by Pixar Studios with the release of Toy Story in 1995. Although its breathtakingly beautiful computer-generated imagery was seen as tolling a death knell for hand-drawn animation, that has not been the case. As with any new technology, CGI has carved its own niche in the field of animation art and produced a sound market for the release of limited editions and interpretive paintings.

There has also been a very promising sea change in the approach to collecting animation art. The purchases are no longer entirely character driven as they were at first. Collectors aren’t looking for a picture of a Disney character so much as they are interested in a Charles Fazzino 3-D treatment of that Disney character. The name of the artist, once known only to a select few, is now of primary interest to collectors. Thanks to the internet any collector has access to the names and artwork of the great young stars of the future.

An informed collector makes a better customer and is always on the hunt for a favorite artist. The gradual acceptance of doing business over the internet, a practice unheard of a decade ago when it came to purchasing art, has created exciting opportunities for galleries who are willing to invest in the medium. A reputable art gallery that stands behind its work can run a very successful virtual gallery, building up a loyal clientele from all over the world.

Hi Dear,

ReplyDeleteI really prefer your blog..! This blog are very useful for me and other. So I see it every day

.

"Online Art Gallery" . from ArtisticBazaar. | Online Art Gallery that ships in all Europe & worldwide at affordable prices...

Check out URL for more info: - https://artisticbazaar.com/